Stories of Chinatown; Finding the Chinese Spirit in Yangon, Myanmar

Yangon Chinatown has always been a hotspot. Every evening 19th Street turns into a jovial street food bazaar where locals and backpackers feast on beer and barbequed skewers and you find plenty of cheap and cheerful hostels with cool rooftop bars. But Chinatown is more than red lanterns and barbequed pork buns, behind the shophouse facades is the close-knit Sino-Burmese community of Yangon. The block between Sint O Dan Street and Latha Street is where they live, eat, play and pray.

Chinatown in Yangon is unlike any other Chinatown in the world. Here no ornate gates, red lanterns or loud temples. The Chinese presence is more subtle, hidden almost. And for good reason; the history of Chinese in Myanmar is long and complex. The people from the Middle Kingdom came to the golden land long before the British Empire took control. Their business community thrived in the colonial period, but the prosperity of the Sino-Burmese community came to an abrupt end under the military regime. Many fled the country, those who stayed, kept a low profile and blended in.

But these days, a new wind is blowing. Chinese life is no longer confined behind closed doors but can once again spill out on the streets. Character signboards appear on shopfronts, people start learning Chinese, dim sum recipes resurface and every year the Chinese New Year celebrations grow bigger. We meet some of the city's most colourful Chinese residents and quiz them about their craft, the Chinese legacy in Yangon and spirit of this bustling neighbourhood.

1. U Thein Aung . Lion Dance Master

Becoming a lion dancer

As one incense stick burned from start to finish, U Thein Aung would have to remain in a squat position. This strenuous training exercise was to become a lion dancer. It was just one of many exercises that a 13-year-old novice had to endure. “You have to be strong enough to hold the lion’s head and to move with ease”, retells U Thein Aung in China Town’s Sint O Dan street -- the heart of Chinatown.

U Thein Aung became mesmerized by the lion dance as a child. One of his earliest memories is watching the lion and dragon dance performances in the Yangon streets during Chinese New Year. When he decided to dedicate his time to becoming a dancer and trained 6 days a week. Sundays were his only day to relax, joining his friends to play football in the street, going to the movies or explore the streets in Chinatown which were largely overgrown with vines, trees and festooning flowers.

For U Thein Aung he has always loved the traditions and the meaning of the lion dance, not just the display of strength and interesting movement. “The lion symbolises good luck,” he explains, “the martial artists would put on the lion head and perform for their teacher, elders or someone they’re thankful for.” The Dragon and Lion Dance Association of Yangon was formed in 2006 when the country became more open. It is led by U They Aung who oversees their training. The team of 20 doesn’t just perform for Chinese New Year, but they also take part in international lion dance competitions. Chinese New Year celebrations continue to grow in size and popularity in Myanmar. A more expensive community of Burmese locals who previously didn’t take part in years under the former military regime, now visit Chinatown as the streets light up during the festival.

Tradition & Innovation

The training from U Thein Aung’s childhood differs to the contemporary training. He laments that “kids these days don’t have any stamina.” There are no hour-long squat exercises or gruelling fitness trainings. Instead the team usually only train a few hours a day in-between their day jobs and study.

However, one thing that has changed over the years is the new heights and leaps that dancers are taking in their routines. “They are very adventurous alright, but compared to us when we trained, their strength can be questionable.”

Next month the Yangon lion dance team will compete at the world championships in Malaysia. In the competition teams perform the traditional lion dance on poles two metres above the ground. Judges award points for the timing, technical skills and overall movement composition. U Thein Aung says Myanmar is always viewed by other country teams as one of the most adventurous teams. “The world is very interested in Myanmar right now, there are so many powerful skilful moves to perform on these poles.”

He’s confident that Myanmar can secure a placing at the competition because this year they have been breaking away from previous dance routines. While he bristled at first when he saw the new approach of the dancers but says proudly that teachers in Myanmar “give the chance for kids to innovate”, which makes them stand out on the world stage.

The Myanmar lion dance team is always viewed by other country teams as one of the most adventurous ones.

2. U Tun Myint . Chief Librarian

Chinese upbringing

“When I was at school if I spoke one sentence in Burmese you’d be fined five cents”, recounts U Tun Myint, now 60 years old. In downtown Yangon the 1960s there were two Chinese schools - Nan Yang Secondary School and Chinese secondary schools - that only taught their students in the Chinese language.

U Tun Mint’s dream was to become a teacher. When asked what draw him to the profession at an early age he writes one phrase in the Chinese script on paper, and instantly the interview feels more like a class than a conversation about his life. Tapping the phrase with his pen he states enthusiastically, “teachers are the engineers of the human souls”.

However, his hopes to become a teacher were crushed when all the Chinese schools were closed down by the government. Under the military regime a policy of elevating Burmese culture over all minorities was exercised across the country. Speaking in native languages or recording one’s indigenous history that wasn’t Burmese could lead to punishment.

“My dream was to become a teacher, they are the engineers of the human soul. My hopes were crushed when all Chinese schools were closed down by the government.”

A Burmese name

At the age of 15, U Tun Myint was sent to a Burmese secondary school to continue his studies and he was forced to choose a Burmese name. He decided to pick a name similar to his favourite celebrity at that time, Tun Wye, so he chose the two words Tun Myint.

Despite having high grades Chinese students who didn’t have Burmese parents were also blocked from entering the national university in Yangon. So, to navigate the system U Tun Myint chose the only course he could gain entry to: studying zoology in Shan State, in eastern Myanmar. There were many cultural differences he experienced on day one of university, such as differences in everyday dress. To gain respect many students wore suits, so U Tun Myint borrowed two from his father to fit in but he added, “If I was wearing suits in Yangon to school everyone would have thought I was mad! But I did it to fit in.”

After university he did odd jobs: ran an ice-cream business, plastic bag manufacturing before finally becoming chief librarian at the Sino-Burmese library on Mahabandoola road.

When I was at school if I spoke one sentence in Burmese you’d be fined five cents.

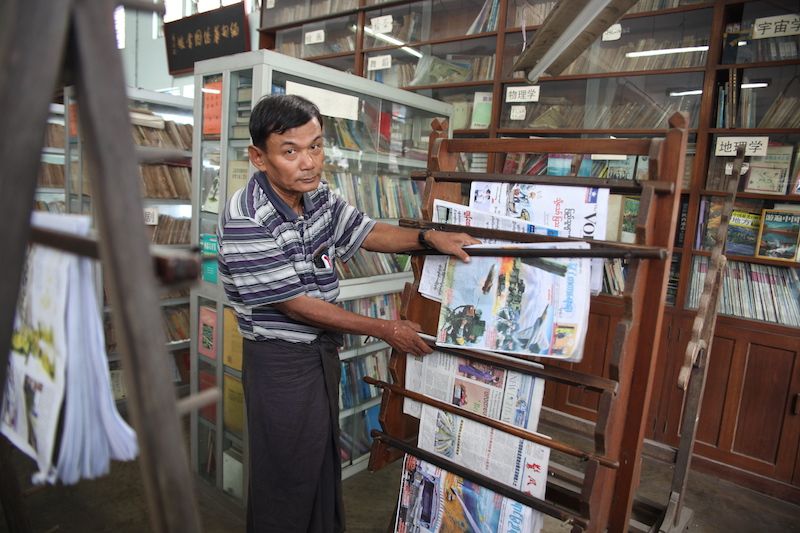

A community library

The library is modest, no more than a couple of hundred books written in Chinese. In the corner sits a small tv and armchairs. There’s a constant crackle of news bulletins broadcast from Chinese state media. You can always count on most chairs being occupied by older gentlemen heads locked in a firm gaze at the TV or others with newspapers sprawled out over the arm of their chairs. The library is a hub for Chinese Burmese elders to keep their Chinese culture alive. Many have recorded their ancestry and written articles on their experiences in Myanmar for overseas publication.

U Tun Myint has found a certain level of contentment, a teacher of sorts to visitors who come to the library wanting to learn more. “There are people from other countries like Malaysia, China, Singapore. Before no one was interested in my life, now after becoming chief librarian I feel like a celebrity.” Perhaps fulfilling the prophecy of his name that he chose from singer Tun Wye.

3. Tan Xin Khoon . Mr. Fix-it

Always a helping hand

“I first gave blood before I was technically the legal age,” retells Tan Xin Khoon, in his home on Sint O Dan street. “The headmaster at my school needed to urgently collect blood as his daughter had an abortion and she was losing blood.” The then 15-year-old, raised his hand and volunteered to donate his blood without a second thought. That was the first of over 40 times he has donated blood. Tan Xin Khoon is the person to go to if you have a broken fan, but also if you need an emergency blood donation.

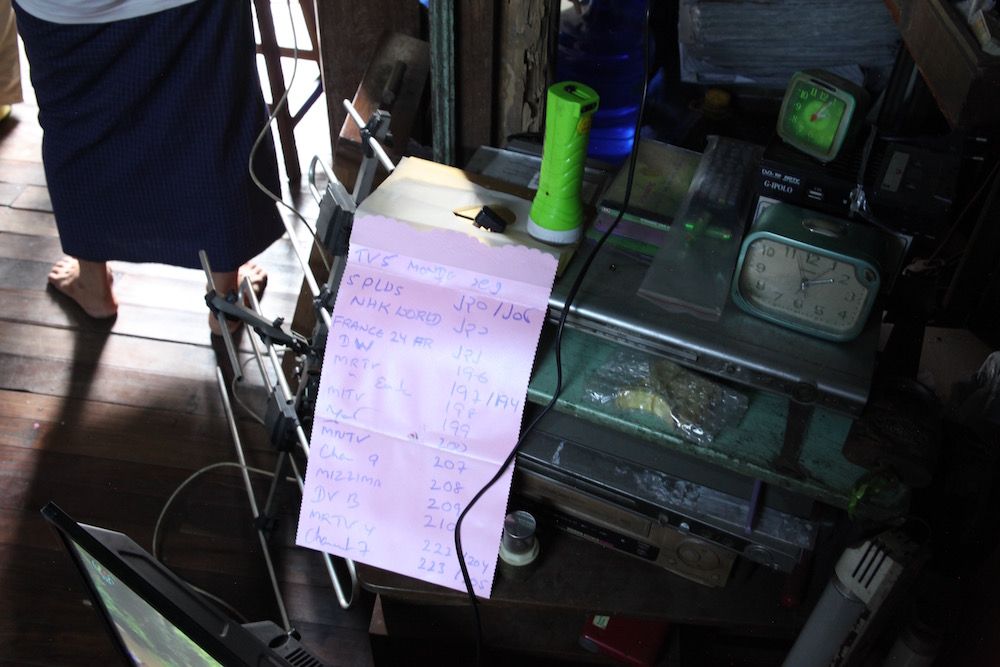

As soon as you walk through the door to Tan Xin Khoon’s home there are cluttered, yet organised piles of books, electrical extension cords and tools. Above his portrait of Aung San Suu Kyi lies a row of staplers perfectly spaced one hand apart on a shelf. Two clocks. An aerial. A buzzing TV in the corner with the local news bulletin. And snug in the corner is a small trophy awarded thanking Tan Xin Khoon for his high number of blood donations to the community.

The trees are gone, it used to be overgrown like a jungle, but now it is a concrete jungle.

Not only does he donate blood but he also organises others. Yangon hospital doesn’t have a computer system to record donors’ profile, but Mr. Fixit keeps them all, tidily in a small box with all the names that he can call whenever stocks are low. He became the general hospital ‘Mr Fixit’ when he first found a problem with the fridge that holds the blood bags. After learning basic electrician skills in an intense 4 months course he then decided to train others around him. When a single mother or young women call for help, he also refuses to accept payment. “I just want to help when I can,” he shrugs.

Chinese heritage

His family history in Chinatown goes back decades. His great-grandparents migrated from Mongolia and made their way through China and settled in the Kokang region. Two portraits of his parents and grandparents sit perfectly aligned on the wall with a small shrine always lit. When asked what he has noticed that has changed the most in Chinatown, he looks at the window to the pavement and states, “the trees are gone.” Not taking his eyes off the street he continues, “it used to be overgrown like a jungle, but now it is a concrete jungle.”

His most prized possession? He’s not sure, but one item he always keeps on him is his card which declares his body is to be donated after he dies. A selfless act planned even for after his death.

4. Aung Kyaw Moe . Baker

Year of the rabbit

In a nondescript stall on the corner of 19th Street hangs a humble sign written in Chinese and Burmese with the symbol of a rabbit. Don’t let the rickety signboard fool you, this is one of the most famous bakeries of the country, supplying pastries to supermarkets and other bakeries all around Myanmar. Little did we know that this small family workshop turns out hundreds of its signature flaky pastries every day.

Ten workers form a production line are the diameter of the shop. One worker rolls the dough, another inserts a ball of peanut butter in the center and the last one brushes the dough with egg yolk, Aung Kyaw Moe explains, “this is a Tai Yang Bing (“Sun pastry”), Dan Wang Su (Egg Yolk pastry), Taro pastry from Taiwan.” These two recipes reveal part of their family history. During the military regime era under General Ne Win the Chinese experienced discrimination and restrictions. It was difficult for us to set up a business and Chinese schools were closed down. As a result, his father fled to Taiwan and learned baking. When he came back, he opened a small bakery. It was 1999, the year of the rabbit.

The pastry recipes reveal part of our family history.

Swimming champion

Aung Kyaw Moe is not your average baker. Before taking over the oven mitts in the family business he told his father, “I want to be a swimming trainer.” However his father quickly scolded him and slowly crushed this dream. Aung Kyaw Moe took an interest to swimming at a late age, diving in at age 18 to the pool to train professionally. He went on to win three silver medals at the Asian Games. But just three years later his father told him his time was up and asked him to take a lead in the family business, Before taking over the oven mitts in the family business he told his father, “I want to be a swimming trainer.”.

Aung Kyaw Moe still swims, he shares reluctantly as he shows us his medals and photographs. But these days most of his time is spent managing the bakery. Especially in the run-up to Chinese New Year things get busy here.

5. Wong Guai Yin . Clanhouse Custodian

Keeping appearances

“This clan house is over 100 years old,” says house keeper Wong Guai Yin as he gives an informal tour of the building. “We come here to hang out, eat food together and gather for celebrations like Chinese New Year.”

Most Chinese families in Chinatown belong to an ’association’ or a ‘clan’. The clan house doubles as a community space where people gather to play mahjong, pray or just hang out and drink tea. Now you can spot the clan buildings on the streets of Chinatown with their elaborate gold-plated character plaques, but in the old days there were more hidden. Very often the ground floor of the building – which is usually the most sacred part of a clan house – would be rented out as shops, particularly electronics of hardware shops, a pragmatic choice to help preserve the future of the association. Wong Guai Yin shrugs “perhaps it means we’ve adjusted to the Burmese influence, they put the most important things high up.”.

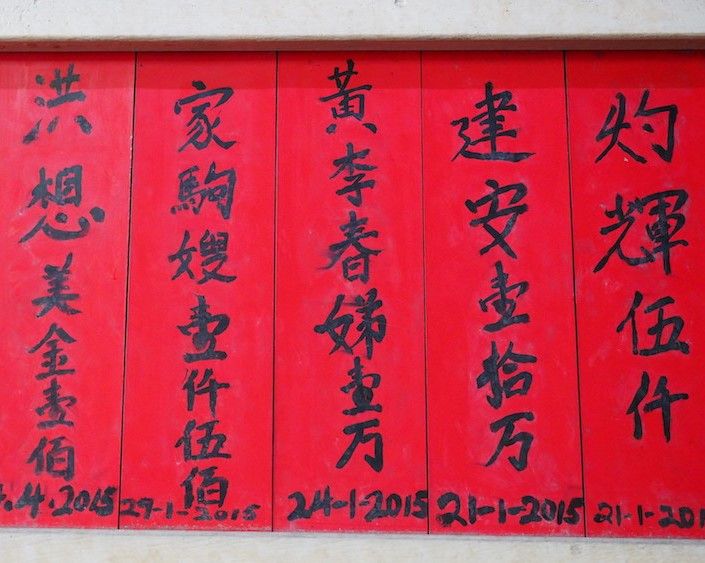

The Wong family clan house is one of the best kept on Bo Ywe Street, with the family name featuring prominently on the intricate balconies. But not all clan houses in Chinatown are so well kept, many are empty, after their families moved away, dilapidated even. Yet, their associations have no intention of selling these properties, quite the opposite, they receive regular donations to polish the furniture ready for the annual Chinese New Year family gathering.

Family secrets

Seventy-one-year old Wong Guai Yin points out the many Chinese script wall hangings that line the entire perimeter of the structure upstairs in the communal hall.

“The interior decoration was all made by our ancestors. We didn’t renovate it at all. This door is from mainland [China]. It’s all antique.” Anyone can join the Wong Family Association; a membership is 500 kyat ($0.50). Many of the Wong family members now live in Hong Kong but still visit often.

Every wooden chain inside has the neat engraving of Wong Family Association and the communal hall is decorated with celebration flags and old photographs that hint at the golden years for the community when many celebrations were large scale events at the Association with live bands, singers and dancing. Wong Guai Yin follows a strict routine of rising with the sun, Burmese traditional mohingya catfish soup or kao soi coconut noodles then he oversees the clan house until midday before retiring for a snooze.

He says there have been a lot of changes over the years and adds that most people speak Burmese now rather than Chinese on the streets of Yangon Chinatown. However, Wong Guai Yin still buys one of the only Chinese newspapers that still exists, the Golden Phoenix. While most members are Chinese people, many have different surnames and have heritage reaching back to different provinces across China. Most are Huang Zhou, Hakka, Fujianese but Wong Guai Yin adds, “anyone is welcome to come in.”

The interior decoration was done by our ancestors. We didn’t renovate it at all. This door is from mainland China. It’s all antique”

Community storytelling

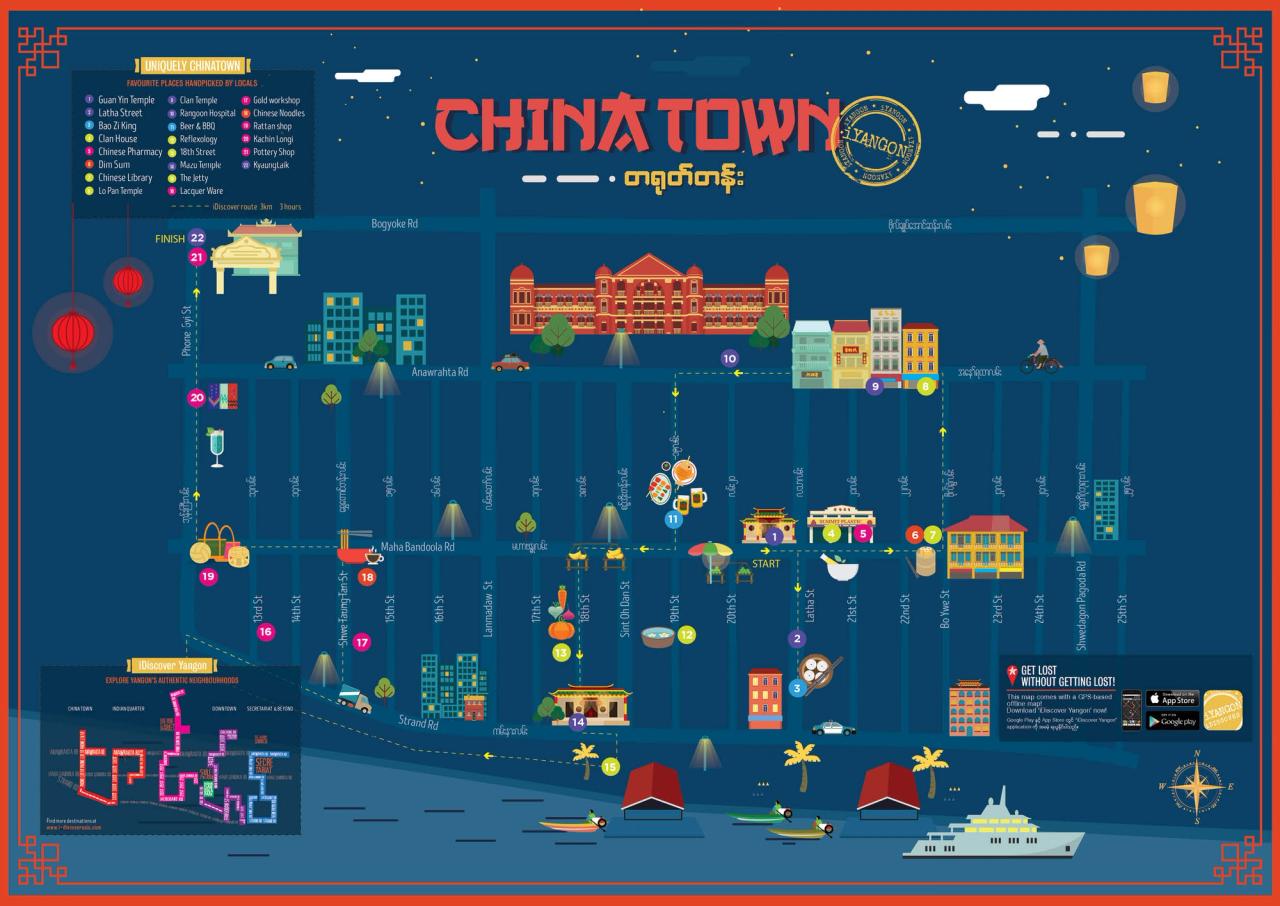

These portraits were part of a community storytelling project in Yangon Chinatown organised in 2020 in collaboration with Doh Eain, a social enterprise that helps owners of historical buildings to renovate their properties and keep local heritage alive. This illustrated map by local designer Mekong Kyaw Swar comes with a walking tour that shows the best of Yangon Chinatown. Stories written by the talented team Libby Hogan and Thurein Tint.

Credits

Powered by

Designed by

Words by

About

Doh Eain ဒို့အိမ်

Doh Eain is a social enterprise that helps residents to restore buildings and design public spaces to make their city more vibrant, inclusive and sustainable. Doh Eain is a social enterprise that helps residents to restore buildings and design public spaces to make their city more vibrant, inclusive and sustainable.

www.doheain.com/enMekong Kyaw Swar Mekong Kyaw Swar

Mekong is an art director and illustrator who handcrafts minimalistic elegant works of Burmese heritage and sunny landscapes out of his hometown Yangon. ဗီယက်နမ်ဇာတိက Mekong က ရန်ကုန်မှာ နေထိုင်သည်။ တရုတ်တန်းက ဟနွိုင်းမြို့ကို အမှတ်ရမိသည်။

@mini_mekongLibby Hogan Libby Hogan

Libby is a freelance journalist who documented the changes across Myanmar's many ethnic states in the past three years after Aung San Suu Kyi won elections. Her passion is looking at youth culture and stagleaping to isolated regions to hear untold stories from those who never had access to media or the opportunity to speak freely. She is now based in Hong Kong where she works for Reuters.

www.libbyhogan.com