Lauded Legacy or Contested History? A Critical Look at Dutch Colonial Heritage in Sri Lanka

In 2024, the Netherlands returned six pieces of looted art to ‘their forgotten colony’ Sri Lanka, including the famous golden Cannon of Kandy. This act began a transformative process that will reshape museum collections as we know them and redefine how we tell the stories of a colonial past. While this restitution is laudable and painful, it extends far beyond technical facts and historical merits. In today's multicultural Netherlands, the act of returning these objects carries great political, cultural and psychological significance. But how do these repatriated artefacts shape Sri Lankans’ sense of history and identity today? And how can this process help the Dutch re-examine their colonial history through a more critical and nuanced lens?

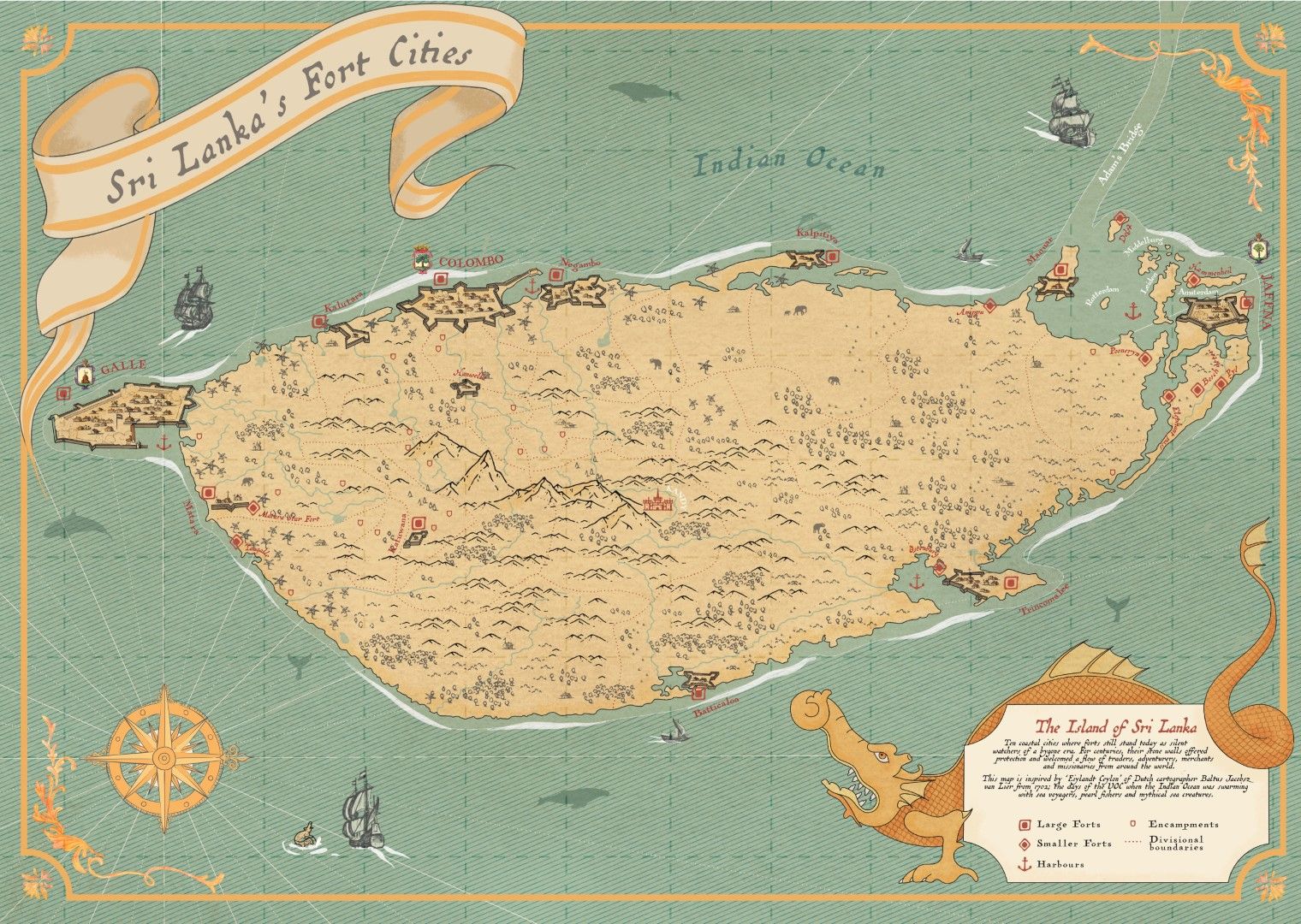

To dig deeper into these questions, we initiated a project that travelled along Sri Lanka’s coastal belt; the ‘fort cities’ of Galle, Colombo, Matara, Trincomalee, and Jaffna, to investigate local sentiments and post-colonial narratives. In these cities, the VOC (Dutch East India Company) colonists erected formidable forts—often on religious or sacred sites—that serve as enduring reminders of colonial rule.

Collaborating with 100 young participants from Sri Lanka and the Netherlands, we examined how Dutch heritage resonates in contemporary Sri Lanka. Our goal was to understand how the colonial past persists in the present and what it means for the future.

The Legacy of Colonial Rule in Ceylon

While most people are familiar with Indonesia’s Dutch colonial past, Sri Lanka’s time under Dutch rule is not common knowledge. Sri Lanka, then known as ‘Ceylon’, is scarcely mentioned in Dutch history books, and is not even featured in the Canon of the Netherlands. Ironically, any Sri Lankan school kid can readily recite the names of Dutch governors, as the ‘Dutch period’ is an integral part of their historical education. Sri Lanka has been under colonial rule for over 400 years, far longer than many other Asian countries, with the Dutch playing a significant role.

In 1638, the King of Kandy asked the VOC (Dutch East India Company to help expel the Portuguese, who had already colonised the cinnamon-rich coastal areas and sought to take control of the whole island. Following two decades of conflict, ‘Dutch Ceylon’ entered the history books. For the next 150 years, the Dutch took over the coastal areas to protect their trade interests in the Indian Ocean. The ports of Colombo and Galle became important stopovers for VOC ships en route to Batavia (now ‘Jakarta’), the capital of the then-Dutch East Indies. When the VOC went bankrupt, the British took over colonial rule until Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948 along with India and Myanmar.

The Dutch colonial imprint is still deeply embedded in Sri Lanka’s coastal cities; streets, towers, bridges, fortresses, churches, markets and warehouses are prominent physical reminders of a painful past. Beyond architecture, the colonial influence extends to administration, law, religion, trade, and almost all social, cultural, and economic customs. Portuguese, Dutch and British elements found their way into everyday life in Sri Lanka; language, food and dress. Surnames like De Vos, Wouters, De Silva, and Mendis are common, and the ‘Burghers’- a distinct ethnic community - are descendants of European settlers.

Confronting the Raw and Painful Realities of Colonialism

The 17th century is often celebrated, glorified even, as the ‘Dutch Golden Age,’ a period defined by the Netherlands’ global maritime and economic powers, artistic achievements, and scientific advancements; think of the capital’s famous canal houses, the invention of the telescope and Rembrandt’s paintings. However, the fact that this accumulation of wealth had come at the cost of colonial violence and transatlantic slave trade was well known, but did not dampen the sense of superiority. For decades, the East and West India Companies that made the Netherlands a world power, were a source of national pride. In 2006, the then-prime minister Jan Peter Balkenende urged the Dutch citizens to take inspiration from the “VOC mentality”. A 2019 British survey revealed that out of all European countries, the Dutch took the most pride in their colonial history, with 50% viewing colonialism positively and a mere 6% considering this part of the past to be shameful.

Yet, in recent years, there has been an unprecedented surge of publications, documentaries, debates, movies and exhibitions that present ‘the other side of the discourse’. They not only reveal new evidence but also articulate critical perspectives on for example, the legacy of the transatlantic slave trade from West Africa to the plantations in the Americas, the apartheid regime in South Africa, the brutal suppression of Indonesia’s independence movement, and the extreme violence of Dutch military campaigns.

In the groundbreaking exhibition “Slavery” (2021), the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam scrutinised its own collection to reveal how the slave trade permeated every level of society, both in the colonies and on home soil, and left a legacy that still ripples through the country today. The 2018 publication “Words Matter” led to a comprehensive linguistic overhaul of colonial-era terminology in museum collections across the country. In 2022, the Royal Institute of the Tropics rebranded itself as the ‘World Museum’ to “move away from colonial connotations and better reflect its position in contemporary society”. They opened the permanent exhibition “Our Colonial Inheritance”, offering a multi-voiced perspective to show how colonialism is not simply ‘a thing of the past’.

The Amsterdam Museum followed suit—and made waves—by replacing the term ‘Golden Age’ with ‘17th century’ to present a more holistic and inclusive narrative. The Van Abbemuseum, a private museum for contemporary art in Eindhoven, took an even bolder step. The museum commissioned a Congolese art collective to create works made of cacao, sugar and palm oil for the exhibition “Two Sides of the Same Coin”. These works were placed as interventions in the existing collection to critique its founder’s wealth, amassed through trade in Sumatra..

The public representation of the Golden Age and its heroes has changed to create an inclusive shared memory that is resistant to and includes post-colonialist critique.”

The critical reassessment is not just about re-examining the past but also articulating pathways for the future. A great example is the “Anti-Canon”, a collection of 50 ‘colonial horror stories’ that every Dutch person should know, which was published by de Volkskrant, one of the country’s leading newspapers. The “Arus Balik” programme at the New Institute is another meaningful initiative that examines colonial legacies in architecture and design between Indonesia and the Netherlands.

We challenge why some people and moments get glorified in the history books and others are not.

A decade ago, such institutional shifts would have been unthinkable, but grassroots activists gave a voice to and propelled the anti-colonial sentiments in Dutch society. The long-standing controversy over “Black Pete” (‘Zwarte Piet’) intensified in the wake of the ‘Black Lives Matter’ protests, causing a rift in society and igniting debates on racism and colonial legacies. Protests erupted in different cities and nearly toppled the statue of Jan Pieterszoon Coen in Hoorn. The ‘other side of the colonial discourse’ also saw a great number of ‘ordinary people’ diving into their family histories and revealing very personal narratives tied to colonialism. The Black Archives, for example, which boasts a collection of over 10,000 books, archives and artifacts presenting black and other perspectives often overlooked elsewhere, “Indisch Zwijgen”, a documentary by third generation ‘Indo’s’ searching for their roots and the acclaimed podcast series “The plantation of my ancestors”, made by a descendant of plantation owners in Surinam.

With the scrutiny of new generations, old certainties about Dutch morality are being challenged.”

A Landmark Moment: The Return of Looted Art

In 2020, King Willem-Alexander apologised for the “excessive violence” the Dutch used to prolong their colonial rule in Indonesia. Four years later, the Netherlands took an unprecedented step by repatriating stolen artefacts to its former Asian colonies. This move was prompted by a 2020 report forwarded by an advisory committee that urged the government to “unconditionally” return looted cultural artefacts if requested by their countries of origin. They concluded that ‘The objects were wrongfully brought to the Netherlands during the colonial period, acquired under duress or by looting’.

In total, 478 pieces - such as 'Lombok treasure' from Indonesia and the Canon of Kandy from Sri Lanka - were transferred from the Rijksmuseum and World Museum to museum collections in Indonesia and Sri Lanka. The pieces returned to Sri Lanka that were formerly on display at the Rijksmuseum, are at the National Museum of Sri Lanka. "These objects represent an important cultural and historical value and they are back in Sri Lanka where they can be seen by the Sri Lankan public," said Dewi Van de Weerd, Ambassador for International Cultural Cooperation. It is about addressing historical injustices."

This is a historic moment, it’s the first time … we give back objects that should never have been brought to the Netherlands. But more than anything, it’s a moment to look to the future. We’re not only returning objects; we’re also embarking on a period of closer cooperation with Indonesia and Sri Lanka in areas like collection research, presentation and exchanges.

Skepticism among Sri Lankans

Conversely, some Sri Lankans are sceptical about the motivations behind the restitution and its potential domestic implications. Concerns have been raised that the government might use this incident to divert attention from pressing issues such as the country's economic crisis or to bolster nationalist sentiments.

Historian Alicia Schrikker, who led the research that formed the basis for the restitution and published a volume on the findings with colleagues from Sri Lanka, said that while some Sri Lankans are pleased with the return, others question whether the restitution serves broader political agendas rather than genuine cultural restoration.

Voices on the internet and in the media resonated these critical sentiments, ranging from “Netherlands should have kept it. Very possible these will be stolen or any gold removed and replaced with fake gold,” to “It is utterly reckless to return anything of value to Sri Lanka, which is in a state of weakness and lawlessness. Artefacts were stolen from the National Museum with Sri Lanka politicians involved. No arrests, no suspects.” Indeed several high profile incidents of museum heists and robberies - a.o. from the National Museum - have troubled the Sri Lankan museum sector in the past decade.

Also, despite the media attention, the arrival of the colonial artefacts did not result in higher visitor numbers for the museum. Interviews on-site in April 2024 at the exhibit also revealed a general sense of enthousiasm for display of the canon and other artefacts, but at the same time a sense of disappointment at the general quality and the choice of wording of the explanation displays and videos. Respondents would have liked to see, read and hear more different perspectives and narratives about the history and context of the artefacts rather than single narrative explainers and a video about the transport of the artefacts.

The Double Discourse of a ‘Forgotten Colony’

Discussions about Dutch colonial history often center on Indonesia, leaving Sri Lanka’s place in this shared past largely overlooked. Yet, during the Dutch Golden Age, the VOC’s trade monopoly on cinnamon, which was a highly coveted commodity, was a major source of profit.. In his book ‘Cinnamon and elephants’, historian Lodewijk Wagenaar describes Sri Lanka as the ‘forgotten colony’ and indeed, even in the Netherlands, few people know that the country was ever colonised by the Dutch.

Equally surprising is that the Sri Lankans have a rather rose-tinted view of ‘the Dutch period’. Dotted along the country’s southern coastline are ample establishments proudly and loudly using Dutch and VOC references in their signage, marketing and menu choices. ‘Dutch architecture’ is even a major selling point for those that own and operate properties. Tharanga, a tour guide in Galle explains: “At school, we learn that the Portuguese were bad; they destroyed temples and holy sites, plundered the land and did not leave much behind. The Brits invested in infrastructure and education, but their interventions also led to deforestation.” Somehow, the Dutch seem to have claimed the sweet spot: “The Dutch gave us a legal system, and built drainage and canals to make the inland more accessible. The Dutch Fort also protected us from the tsunami.”

The story of how the Dutch ended up in Sri Lanka sounds innocent. After all, they were invited by the King of Kandy to expel the Portuguese. Yet, of course the Dutch came with ulterior motives. After their victory, they told King Raja Sinha II: ”We are here to help you, Sire, but we will not leave until you reimburse the costs we incurred by waging war for you.” They demanded millions of guilders, which the King was in a position to pay. From then on, for nearly a century and a half, the VOC took control of almost the entire coastline and turned the island into a lucrative colonial outpost.

They cultivated and exploited the coastal areas, erased large swaths of forest and paddy fields for cinnamon and pepper plantations.They also capitalized on Sri Lanka’s elephant trade, exporting the animals to India.. The Dutch used a clever combination of their military might and soft diplomacy to appease the kings with annual emissaries sent to the Kandy Kingdom bearing gifts. “Annually the Dutch sent gifts worth 25,000 guilders brought from foreign lands, including porcelain from China, furniture from Japan and Persian horses which the king particularly liked.” Dr Wagenaar explains in his book.

This way, the VOC completely isolated its former ally King Raja Sinha II and his successors from the outside world. They were forced to look on in impotent rage while the all-powerful Company exported the islands’ cinnamon and elephants, refusing to share with the inland kingdom any profits from the country’s resources. The Dutch also shipped and sold slaves. Central Colombo’s Kompannaveediya (or ‘Slave Island’) is where the VOC slave barracks were located. Most slaves came from across the Indian Ocean, from what is now Indonesia, Bengal and Kerala in India. Historians suggest that in the 18th century, around 800 slaves must have lived on Slave Island. It was a community of considerable size, whose offspring continued to live there for generations to come. Even today, the area is still home to Malays and the descendants of the slaves who were shipped there in the Dutch period.

And there were battles. Resistance against the Dutch grew over time; around 1760, local farmers started to protest against the forced labour on the cinnamon plantations and the capturing of elephants. With tensions rising, the king ordered an attack on Matara, which started a guerilla war. By March 1761, Kandyan forces and rebellious lowlanders occupied the Matara Fort, forcing the Dutch garrison to evacuate to Galle. Matara was occupied for nearly a year before the Dutch recaptured it. As a retaliation, VOC forces invaded Kandy in February 1765. Although their victory was short lived, the damage they inflicted was severe: they slaughtered holy cows, destroyed Buddha statues and plundered the royal temple and palaces. Among the stolen treasures was the Kandy canon.

By the late 18th century, however, the VOC was almost bankrupt. Just as he had once enlisted the Dutch against the Portuguese, the Kandyan king now approached the British to get rid of the Dutch. Between 1761 and 1765, the Dutch put up a fight, but by 1796, they were forced to surrender to the British, bringing an end to their rule in Sri Lanka.

A Cultural Investigation in ‘Dutch Fort Cities’: iDiscover Field Schools in Sri Lanka

To find out more about the perspectives and connotations of the Dutch legacy in Sri Lanka, we designed a mapping and storytelling project with students and young professionals in the ‘Fort Cities’ along the coast. Across three fieldschools, a total of 100 students from diverse disciplines - cultural heritage, history, archaeology, architecture, museum and media studies - worked together to interview residents and business owners about important and unique places in their locality. The students investigated different historical and cultural layers of these places, and went searching for the stories, memories and different perspectives. Through a pop-up exhibition, the students then shared their findings, bringing the stories back to the community.

The resident surveys in Galle, Matara, Trincomalee and Jaffna revealed that the (remains of) Dutch forts are well-known sites among locals and perceived by the large majority of respondents as key landmarks in the city. Other reminders of the Dutch times, such as the Dutch Church and Hospital in Galle, Dutch Bay in Trincomalee, Dutch Market in Matara and Dutch Town in Jaffna, were frequently mentioned, even though some of these sites technically do not even date from the Dutch period. Street surveys reflected little negativity about the colonial past; very few respondents were outspoken in their critique. Quite on the contrary, in Galle, for example, ‘Dutch architecture’ was perceived synonymous with colonial elegance, and the popularity of ‘Galle Dutch Fort’ as a tourist destination was envied by many residents of the other Fort Cities. When we asked Jaffna residents what they wished for their city’s fort, an overwhelming majority of respondents wanted it ‘to develop like Galle’.

We also found that knowledge of what happened in and around these forts in the colonial period was not well known. For example, few of the interviewees knew that it twas a military base rather than a residential site or that Matara Fort was used to house elephants. Or that Matara Fort was the site of a major battle, where the Kandyan soldiers defeated the Dutch, prompting the colonists to build an additional Star Fort for protection against inland attacks. In addition, Sri Lanka’s cultural divide means that few young people get the opportunity to travel within the country, even though it is relatively small. Most of the field school participants from the North and East had never visited the South.

All of us, Tamil and Sinhala got to spend time together. We ate together, roamed around together, and got to really get to know each of our histories.

A final observation was that these heritage sites have different connotations for different people. Surrounded by myths, legends and stories, these historic places often have multiple layers and narratives. For example, Fort Frederick in Trinco is a nature reserve, military base and pilgrimage site all in one. It is best known as one of the most important sacred sites in Hindu religion - the ‘Rome of the Pagans of the Orient’ - home to the massive Koneshwaram ‘Temple of a Thousand Pillars’. It also holds great significance in Buddhist religion and is linked to the tragic love story of Francina, the daughter of a Dutch army commander who fell in love with a Dutch soldier. The original temple no longer exists; the holy site was destroyed by the Portuguese, who looted the shrines, sank the pillars into the ocean and used the rubble to build a fort, which, even today, is still used as a military camp. Every day, a procession of Hindu pilgrims walk along the ramparts and across the parade grounds to pray at the Swami rock, which now features several smaller temples and statues. Adding to the surreal atmosphere of the site is the presence of abundant deer, the only such population in the country

A Multilayered Past Leads to Multiple Perspectives

For the participants, it was an eye opener to conclude that there is no single perception of a place—historical narratives vary depending on ethnicity, religion, age, or gender. Many students had a deep understanding of particular places from their own cultural perspective, but never had the opportunity to share their insights with peers from different backgrounds. Unravelling these layers and exploring alternate narratives was a big part of our project. With the help of the facilitators, creative storytelling methods and even Google Translate, the participants were challenged to “unlearn” preconceived notions, accept each other’s perspectives, and move forward together. The course equipped youngsters—Sinhala, Tamil and Dutch—with the historical knowledge and cultural experiences necessary to reflect on the history and significance of a Dutch Fort and develop a more comprehensive understanding of a place and its identity. This also led to a newfound appreciation for colonial heritage—not only because it makes these fort cities unique within Sri Lanka but also because this heritage remains underexplored, with countless stories and structures waiting to be rediscovered. Such efforts could bridge different cultures and perhaps even contribute to cultural reconciliation.

Even though this is my hometown, I wasn't familiar with anything in Trinco. I’ve never really thought much about the cultural significance of these places and what it means to each of us. Talking to people and understanding really opened my eyes to so many sides of the same incidents.

Now we know the true potential of this fascinating place. If we let go, we may lose it forever. But if we conserve and improve it, this palace can be even better than Galle Fort.

Post-Colonial Narratives: The Other Side of History

The field schools also opened up conversations about the relevance of local heritage and shared colonial history and how it impacts cultural identity and diversity in the present day in light of the post-colonial discourse, specifically on the current discussion of the restitution of stolen artefacts to Sri Lanka. One major realisation was that while the Dutch are only just beginning to come to terms with their colonial past, the participants observed that Sri Lankans, the people on the other side of the discourse, have long been doing so in various ways: by removing, reinterpreting and reinventing heritage sites and stories; the good, the bad and the ugly.

“Sri Lanka has been through a lot—from natural disasters to decades of war and economic instability. The people here are incredibly resilient. One can always focus on the negatives, but our people choose to emphasise the positives and to deal with the cards we’ve got.” concluded one of the mentors. He illustrated this with an example: what an outsider might perceive as ‘foreign colonial influences’—such as Dutch names, dress, or architectural styles—often feel like an intrinsic part of Sri Lankan culture today.

“The (Galle) Fort was built for war, but now you see couples and families gathering there, turning it into a place of love. It’s fascinating how a place can evolve so drastically over time.” – Devni (35)

In these cities, colonialism didn’t just leave behind forts—it fundamentally shaped how people live, who they marry, how their families are structured, and even the languages they speak. - Atheeq (32)

Also, the Sri Lankan students tended to be more future-focused: “What’s done is done. Fixing the past is great, but countries such as Sri Lanka now look to the future. So, that’s where the collective focus should be, and what we can do to improve the future” shared a Sri Lankan participant.

Dutch students, on the other hand, struggled with confronting their forefather’s past. “I feel ashamed of the culture I’m part of. But I also don’t feel like people here hold it against me. Now, we need to shift our focus away from national identity and historical guilt and toward a responsible, forward-thinking relationship with Sri Lanka,” reflected one Dutch student.

Some students questioned whether the term ‘shared heritage’ accurately describes these forts. “I see shared heritage in the architecture and behaviour of people, but I don’t think we can consider the Jaffna Fort itself ‘shared heritage’. It was a product of colonisation and harshness. This also begs the question, is the terminology of ‘shared heritage’ accurate when trying to converse about this topic? While the coloniser and the colonised coexisted, there is a dynamic of an oppressor and the oppressed. Especially considering the initial interaction between the Dutch and Ceylonese, which was transactional, and focused on security and trade” noted a Dutch student.

“I found this [learning] a bit hard because back in the Netherlands, this part of our history is not well known. I now realise how capitalism and colonialism has underpinned our relationship with other countries for so many years, it explains a lot about our position in the world today,” added another student.

The physical remains and presence of Dutch history have left a lasting impact, with, for instance, Galle Fort serving as a bustling tourist and heritage hub.. As a result, some of the feedback we got from the people of Matara Fort was that they wished that the Matara Fort was as lively and profitable as the Galle Fort. “I find it strange that the locals have such a positive view of this colonial past, but I also hope that we don’t forget the actions of the Dutch and the other colonisers in these places,” said one of the students.

Some of the Dutch students also struggled with the concept of cultural appropriation. “Throughout this exercise, I felt like these stories weren’t mine to tell. We can help with research, documentation and other stuff, but ultimately, these narratives belong to the local communities,” said another Dutch student. Yet, others felt that “this learning process and these conversations are more important than the final product. Having immersive experiences like this is the first step toward reconciliation - it’s a shared responsibility. Now, these stories are part of our journey too”.

This goes beyond returning artifacts. You, as young people, become the future of the world. You are the future custodians of heritage. By working in programs like this and rediscovering history, you take on the responsibility of preserving it.

Every journey you make leaves a footprint in your heart. In Sri Lanka, we did not just leave footprints, we also made friendships that will welcome us back as family”

Sri Lanka’s ‘fort cities’ are cities where the future is bigger than the past.

A Future for the Shared Past

To conclude, we asked participants and facilitators for their recommendations on initiatives and programs for young people in coastal cities that could raise awareness about the colonial period and the historical connections between the Netherlands and Sri Lanka. Here’s how they envision the two countries collaborating toward a shared future:

- First, with the return of stolen artifacts, there’s an opportunity to extend awareness beyond the walls of museums and cultural institutions. A multidisciplinary team—including historians, archaeologists, museum experts, anthropologists, educational specialists, psychologists, artists, and creative professionals—should work together to curate engaging "behind the scenes" content such as videos, interviews, cartoons, and murals. This approach would allow for a multivoiced narrative and make learning more about this complicated, layered topic more accessible, interactive, and immersive experience. For example, videos featuring (street) interviews across different demographics and cultural backgrounds could capture local perspectives on the colonial past in both Sri Lanka and the Netherlands. This would also be a worthwhile addition to the displays of the stolen artefacts in Colombo, both current and future ones.

- In Sri Lanka, we advocate for long-term educational projects that allow students to collaborate, discover stories, and create content and exhibitions together. Initiatives like these would enable students from different fort cities to interact and learn from one another. By offering opportunities to visit other fort cities in person, students would gain new perspectives and a deeper understanding of their country’s history. A roving exhibition or traveling field school could facilitate this dialogue between local and international students, as well as elders.

- In the Netherlands, we envision collaborations with (regional) archives and museums in VOC cities, such as the Amsterdam and Rotterdam City Archives, the Maritime Museums, the West Frisian Museum in Hoorn, the Zeeuws Museum in Middelburg, and the Prinsenhof in Delft. By rediscovering the colonial collections through the lens of youth—both Sri Lankan and Dutch—personal narratives of seafarers and colonists would shed new light on colonial history. This initiative would not only raise awareness among Dutch audiences but also empower Sri Lankans to investigate the layered history they share.

Walking the Talk: Exploring Sri Lanka’s Fort Cities

Through our iDiscover field schools, Sri Lankan and Dutch students collectively created 20 digital heritage trails and travel blogs, exploring the history, heritage, culture and myriad narratives that coexist in the Sri Lankan fort cities of Jaffna, Galle, Colombo, Matara, Trincomalee, and Jaffna.

Join them in this journey: Explore their digital maps and write-ups and learn more about the shared histories of Sri Lanka and the Netherlands through their lens. Visit their content, share your thoughts, and continue the conversation—online and in person. Because our colonial history is not just to be remembered; we all bear the responsibility to actively explore and understand it.